How We Got Here: Housing Inequity

Success in life is rooted in a stable home for all ages and all people. When we have safe, secure places to live, parents earn more, kids learn better, health and well-being improve, our communities are strengthened, and our region has the building blocks for a thriving region. So how did we get to the place where tens of thousands of people experience homelessness in the Bay Area? Why are there so few homes low-income people can afford, not just in the Bay Area, but the nation? Why do low-income Black and brown residents experience homelessness, evictions, and are priced out of the neighborhoods they were raised in more often than white residents? Why do some communities that have a high percentage of white residents also have a high number of large, single-family homes? Why is it so difficult for a low-income wheelchair user to find a quality, accessible, affordable home?

This page shares information about how specific aspects of housing inequality came to be.

Table of Contents

Colonization in the East Bay

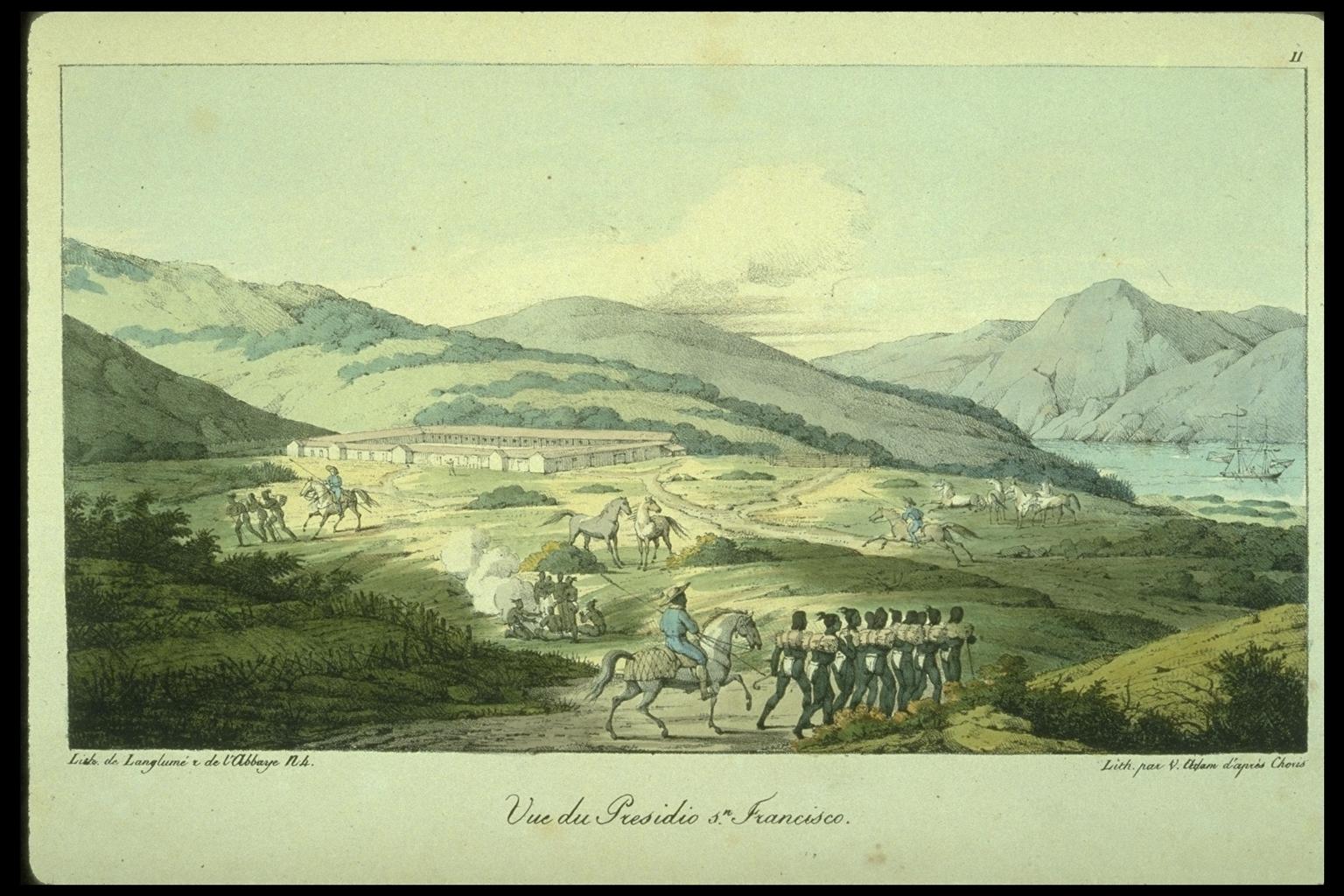

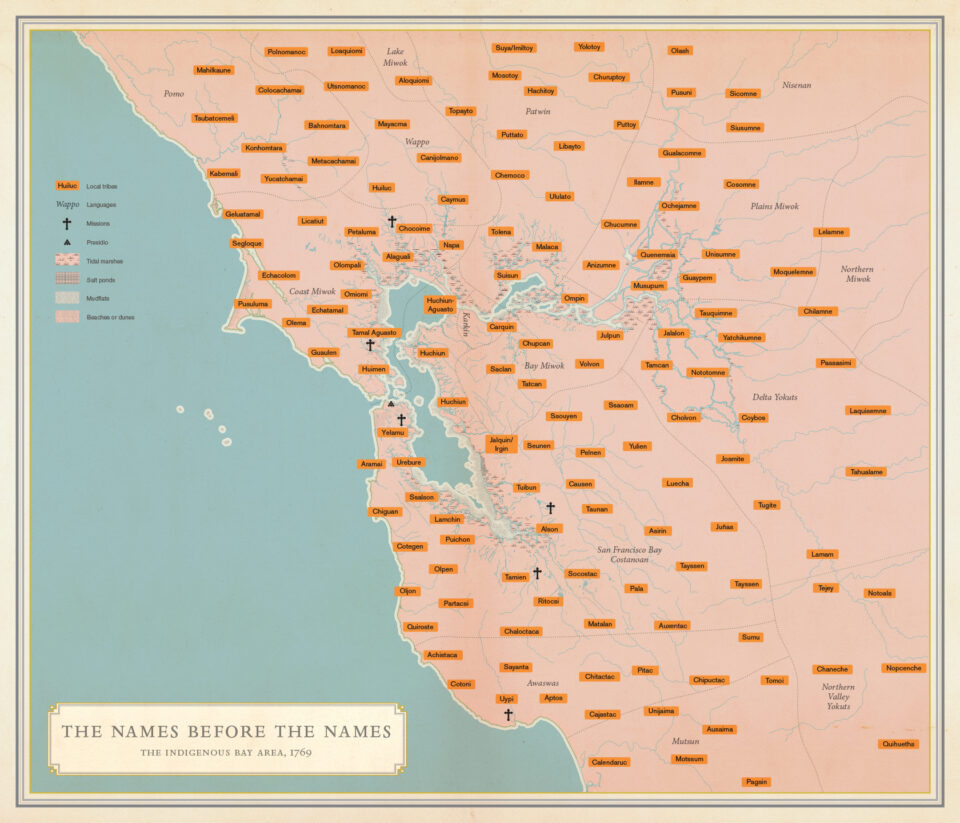

To begin to understand how Huchin Ohlone territory, land that is home to Lisjan Ohlone people for thousands of years, came to be understood by those of us who live here now as cities with names, shaped by streets, buildings and our homes, we must start here.

“Racial exclusion in housing is a systemic process fundamentally tied to the control of land and the power to decide who is able to call a place home. The earliest forms of racial exclusion in the Bay Area were the violent dispossession of Native Americans’ land and concentration of ownership of land by Spanish, Mexican, and early US settlers and governments.” — The Origins of Exclusion: State Violence & Dispossession, The Othering & Belonging Institute.

The Origins of Exclusion:

State Violence & Dispossession

from, The Othering & Belonging Institute

Read more about this history and organizations working for Indigenous rights in the Bay Area in the Bay Area Equity Atlas Native Land Digital Mapping Tool.

An Economy Built on Slavery

The economic foundation of the United States is a foundation of both colonization and slavery. The profit and infrastructure (roads, buildings, farm fields) produced by forced labor and the trade of humans created profit and wealth that are the foundation of the banks and corporations that circulate money and make loans. Land, capital, and infrastructure are what our system of housing is built on, and the U.S. housing market is currently based on housing as a commodity, though it doesn’t have to be this way. The following readings/audio pieces share different aspects of how wealth accumulation and the housing market are rooted in slavery — a painful and necessary truth to recognize and confront if we are to create a future of housing that values Black life and homes; a housing system that is not rooted in extraction and exploitation.

In order to understand the brutality of American capitalism, you have to start on the plantation.

by Matthew Desmond, The New York Times 1619 Project

Ta-Nehisi Coates essay, the Case for Reparations follows a clear line from slavery to housing discrimination. “Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.” — Ta-Nehisi Coates, the Atlantic.

The Case for Reparations

by Ta-Nehisi Coates

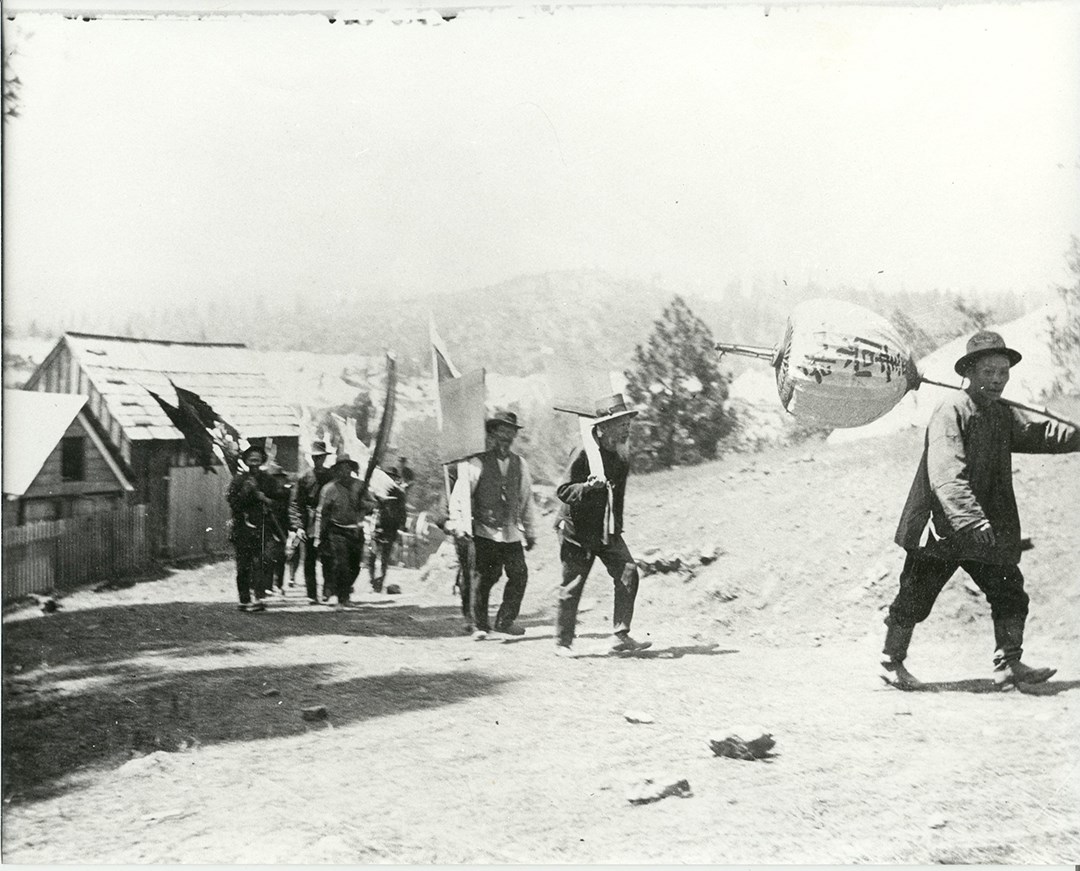

The enslavement of Indigenous people in the Spanish Missions and later the violence and sometimes forced labor of Chinese workers were central to the infrastructure of California that is the foundation of our cities. “They were also toiling longer hours, often under dangerous conditions, whipped or restrained if they left to seek employment elsewhere.” (Chris Fuchs) Immigrant workers from China built the railroads, which are a foundation of the wealth that has formed foundational institutions of the Bay Area. “Leland Stanford, a wealthy former California governor who ran under an anti-Chinese immigrant platform, was also president of the Central Pacific. The railroad made Stanford even richer, and to honor their son who died of typhoid fever, the Stanfords later founded the school that bears their name.” (ibid)

50 Years Ago, Chinese Railroad Workers Staged the Era’s Largest Labor Strike

by Chris Fuchs

Racial segregation in the U.S. has shaped our communities in profound ways. It has impacted racial disparity between white people in the U.S. and Black, Indigenous, Chinese and Japanese and other Asian American and Pacific Islanders, and Latino/x communities. Where one lives in our nation with a history of segregation has impacted inter-generational wealth and stability, who went to well-funded schools and who did not, and who lives in communities sited near industrial pollution and more.

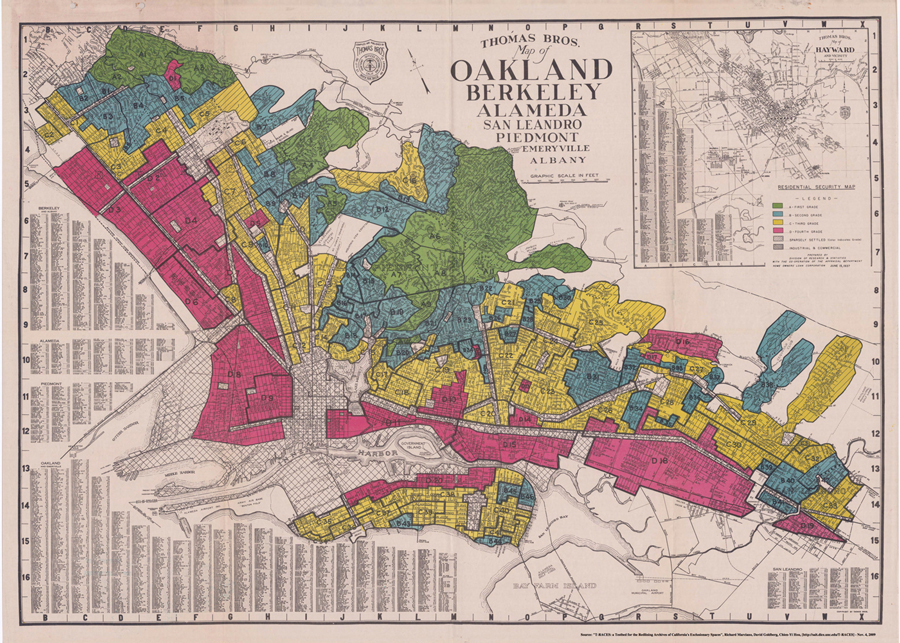

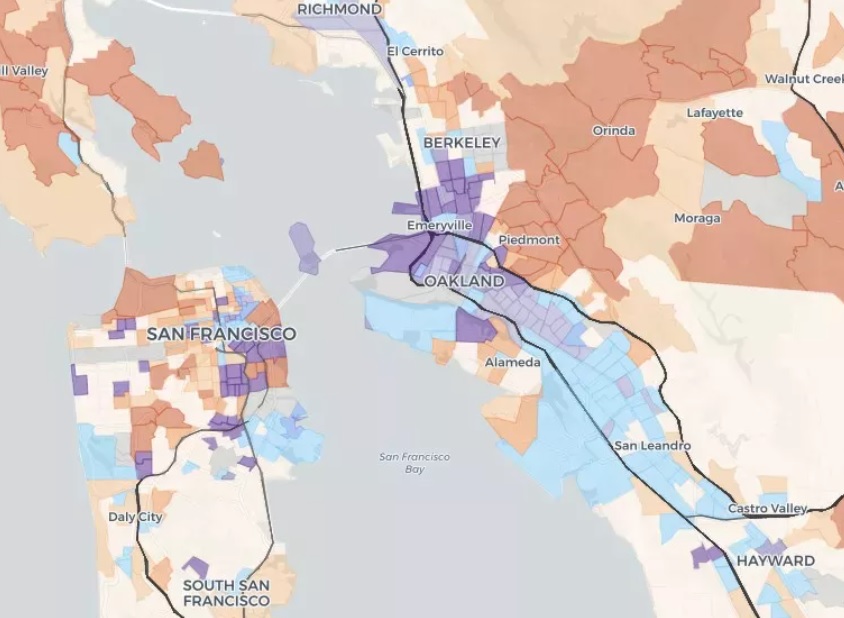

Racial Segregation in Housing

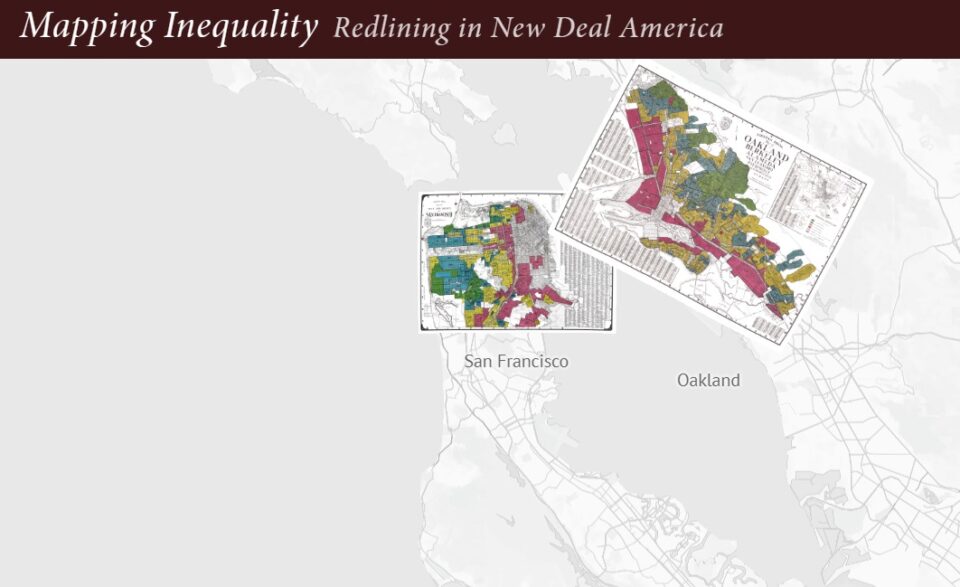

The map above shows neighborhoods color-coded block by block. This is a map that banks used to determine whether or not they would make mortgage loans to people, and at what rate. The color-codes assigned value based on perceived ‘risk’ of the neighborhood losing value on the property of the home, and it also mapped to where mostly white, high-wealth people who have been here for many generations lived (green sections) and Black, Chinese, and other people of color and new immigrants lived (red sections), which sometimes were literally also industrial sites. This forced Black, Chinese, and other immigrant populations into segregated neighborhoods with not enough housing options, driving up the price of sub-standard, segregated rental housing in redlined neighborhoods. The book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, outlines how redlining and racial segregation happened here in the Bay Area.

Above: A video explanation of government and bank-backed housing segregation, https://www.segregatedbydesign.com/.

View Your Neighborhood:

Use the Interactive Map to see how redlining was determined down to the neighborhood level with Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

Housing Discrimination

It was not just the private sector of housing that shaped racial segregation in the Bay Area — wartime housing for soldiers in the Bay Area in World War II was almost all racially segregated. Despite the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, segregation and housing inequity based on race and disability continue to persist.

Even though explicit, written discrimination based on race is illegal, many Home Owner Associations continue to guard choose who is allowed to live in the community and not – this is rooted in real practices, right here in the Bay Area.

Racially Restrictive Covenants & Homeowner Association ByLaws

from the Othering & Belonging Institute’s Roots, Race, & Place report

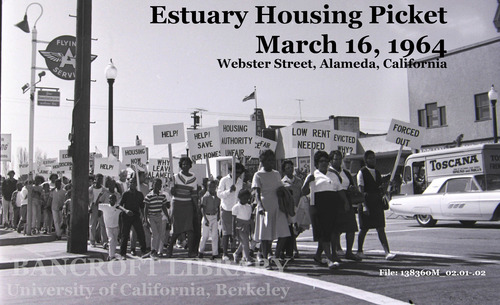

The City of Alameda has a long legacy of explicit racial discrimination in public and private-market housing as well as racist intimidation and violence through organized white supremacist organizations. While it has a specific history in the East Bay of California, it is one of many cities that have similar legacies. The collection of articles below – a city-specific reading list based off the research of Rasheed Shabazz – helps us understand how a thread of racial discrimination in housing weaves from the early 1900’s to the present, taking different forms with similar outcomes.

Historical Context:

Racism & Housing in the City of Alameda

As long as there has been racial discrimination, there have also been people fighting against it. Hear the story of H.O.P.E. in Alameda, whose legacy precedes EBHO member organization, Renewed Hope Housing Advocates.

Many of the sources above describe segregation and outright refusal to lend to Black, Chinese, and other communities deemed “high risk” at fair rates. Sources also describe formalized, written-down exclusion practices, such as racial covenants. However, racial discrimination in housing is not a thing of the far-away past. For example, in 2021, this Black family’s Marin County home was appraised 500k less than when a white woman posed as the homeowner.

Scholar Andre Perry’s Book, Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America examines the historical roots and impacts of this practice.

Sometimes, policies that are intended to help people are designed in ways that have a negative impact; it’s part of why EBHO’s policy team works hard to understand and advocate in the details of how bills are written at the state and local level. Read, When the Dream of Owning a Home Became a Nightmare: A federal program to encourage black homeownership in the 1970s ended in a flood of foreclosures. by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. You can hear a conversation about this research here:

Discrimination against people living in public & affordable housing

While Andre Perry’s book is largely about Black homeownership, there is a long history of majority-white, middle- and upper-class communities resisting multi-family and publicly-subsidized housing in their communities, often laden with anti-Black and anti-poor rhetoric. In California, the ability for communities to discriminate on the type of people that can live in their town based on the type of housing they can afford was written into the state constitution. This statute, Article 34, requires public approval before public housing is built in a community. “The rule stymied low-income housing construction for decades,” says Liam Dillon in this LA Times article.

At the Federal level, after decades of not funding the basic maintenance and upkeep of public housing, the Federal legislature passed the Faircloth Amendment, freezing the number of public housing units and replacing a portion of public housing units with less affordable homes. These state and federal bills are an important part of why we have a shortage of homes that are affordable to people with low-incomes in California and across the nation.

What is the Faircloth Amendment?

by JARED BREY

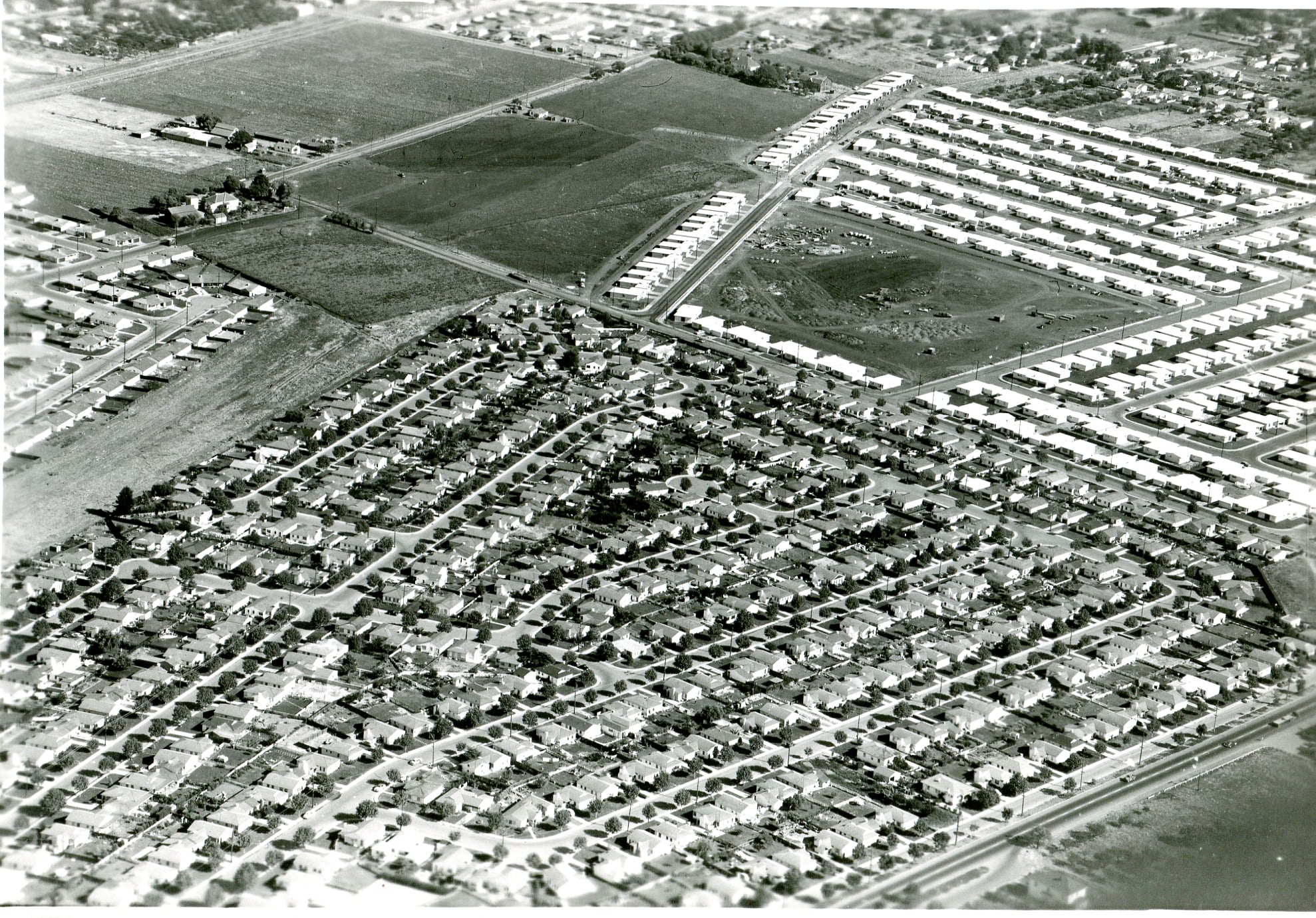

Residents in suburban and predominantly white urban communities across California continue to block the creation of new affordable housing, and this forms a base of constituents that the former president attempted to mobilize when he ran for re-election. Housing reporters Liam Dillon and Matt Levin speak with sociology Karyn Lacy about the link between the discriminatory history of the federal government’s collaboration with private industry after World War II to exclude people of color from mostly white suburbs, and how that history is directly connected 21st century suburban dog-whistles in opposition to low-income housing.

Housing Discrimination Against People with Disabilities

Refusing to rent to a person who has a disability has been technically illegal since 1973. However, structural inequity and ongoing discrimination prevent millions of people with disabilities from finding a quality home they can afford. “Approximately 4.8 million adults with disabilities who are between the ages of 18 and 64 received income from the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program in 2016. The enormity of rental housing costs relative to monthly SSI payments affects the daily lives of millions of adults with disabilities. Unless they have rental assistance or live with other household members who have additional income, virtually everyone in this group has great difficulty finding housing that is affordable.” (Priced Out) The majority of U.S. homes are not accessible to people with many physical disabilities. (HUD)

Priced Out: the Housing Crisis for People with Disabilities

by the Technical Assistance Collaborative Inc.

Housing Discrimination Against LGBTQ People

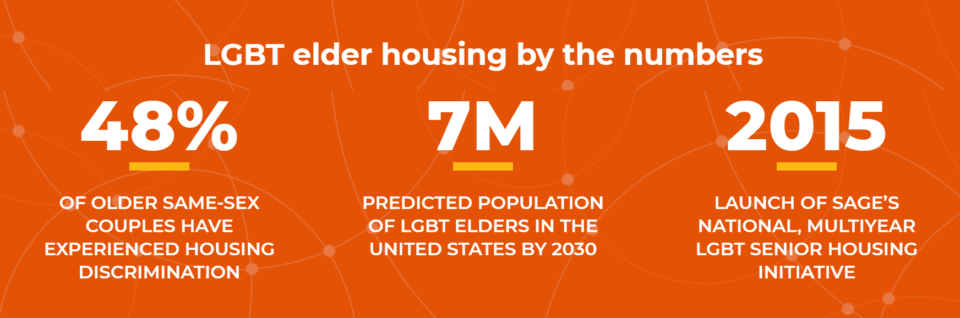

Although explicit discrimination against LGBT people in housing and public accommodations has been banned since 2005 in California, and the Biden administration signed an executive order in January, 2021 banning discrimination against LGBTQ people in housing, discrimination and structural barriers to quality affordable housing persist. The National Center for Transgender Equality says one in five transgender people in the U.S. has been discriminated against when seeking a home, and more than one in 10 have been evicted from their homes because of their gender identity.

The impact of that discrimination, especially for LGBTQ people that experience other barriers to equal treatment such as racism or ableism, has resulted in high rates of poverty and housing insecurity for LGBTQ communities over the last century. For many transgender people, a lack of access to documents, credit history, and rental history in which their names are aligned can create another barrier. An estimated 30% of transgender people have experienced homelessness.

SAGE is a national organization that advocates and provides services for LGBT Elders. View their policy and discussion video below to hear more in-depth about challenges and opportunities to housing equity for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender elders.

Gentrification & Displacement

Rising rents without adequate rental protections have forced many long-time residents, often low- and median-wage workers and retirees, out of the communities they were raised in and have spent decades building community ties in. Even during the pandemic, with eviction moratoriums in place across the Bay Area, hundreds of Bay Area residents were evicted.

Urban Displacement Project

Use this map to see displacement trends block-by-block in your community:

The Impact of Short Term Rentals on Affordable Housing in Oakland

Mia Carabajal prepared for East Bay Housing Organizations and Community Economics Inc. in 2015

No Place for Faith: The Impact of Displacement on Churches

By Rachel Thompson, prepared for East Bay Housing Organizations’ Interfaith Communities United

Read: East Bay Housing Organizations (EBHO) Framing Paper on Gentrification, Displacement and Public Benefits in Oakland.” 2014.

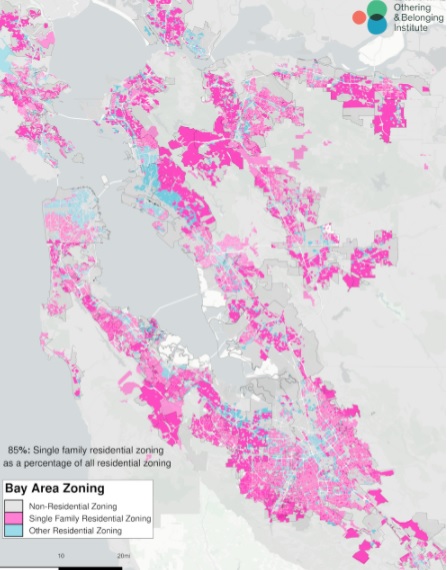

Exclusionary Zoning

Exclusionary zoning is when zoning laws prevent people from living in certain areas in a manner that discriminates by race, ethnicity, religion, income, disability, or another group characteristic. In the early 1900s, real-estate practices such as racial redlining and restrictive covenants were used to explicitly exclude marginalized people from upper-income, White, Christian neighborhoods. Since then, such practices have been ruled illegal. But in their place, many communities have turned to practices such as single-family zoning and other restrictions on multi-family housing that make it harder for low-income people and people of color to live in areas that have the most economic and environmental resources. Inclusionary zoning and Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing policies are meant to reverse the harmful impacts of exclusionary zoning.

Read: The Racial Origin of Zoning in American Cities by Christopher Silver. Originally published in Manning Thomas, June and Marsha Ritzdorf eds. Urban Planning and the African American Community: In

the Shadows. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1997.

Single-Family Zoning in the San Francisco Bay Area

Characteristics of Exclusionary Communities

by Stephen Menendian, Samir Gambhir, Karina French, and Arthur Gailes

In 2020, EBHO was part of a campaign to repeal an exclusionary zoning article voted into the Charter in the City of Alameda. In the video below, historian Rasheed Shabazz shares information about the history of segregation, exclusionary zoning, and displacement as well as stories about the people who organized against these policies.

The Elimination of Redevelopment Agencies in California

In 2011, the State of California eliminateded Redevelopment Agencies, striking a blow to a key funding source for rehabilitating and building new affordable homes.

“The California Community Redevelopment Act of 1945 (later called the Community Redevelopment Law)

aimed to catalyze private investment by allowing a city or a county to designate “blighted” areas and establish an

RDA, which could raise capital for infrastructure improvements by issuing bonds against future tax revenues. The RDA got to keep the difference between the original property tax revenue and the revenue from the improved property (the “property tax increment”). These funds were used to pay off the bonds and capitalize the RDA operations overall.

Amendments to the law in 1976 and 1993 required RDAs to set aside 20 percent of their funding to create

and preserve affordable housing, and required cities to ensure that 15 percent of all housing in a redevelopment area be affordable to low- and moderate-income residents. This allocation supported the preservation and development of nearly 100,000 units1 of housing for low- and moderate-income families statewide between 1993 and

2011, and supported local first-time-homebuyer programs and rehab loans in many cities. The fall of redevelopment has left community-based organizations and housing advocates concerned about how to finance affordable housing. Unless they can be particularly creative in identifying new funding sources and changing political will, the RDAs’ demise may well result in displacement, instability and even homelessness for thousands of Californians.” from Christy Lefall, Gloria Bruce, and Marcy Rein. “Redevelopment: After the Fall” Race, Poverty & the Environment. Vol. 19, No. 1, 2012.

Corporate Speculation and Rising Housing Costs

The wealth-gap between homeowners and renters in the U.S. is large, but when mega-corporations began buying up foreclosed and distressed homes during the 2007-2008 housing bubble and financial crisis, their hold on the housing market increased, contributing to the upward price to buy a home– often offering cash over middle-class homeowners who use a mortgage to finance their homebuying. Not only that, the number of renters living in a home owned by a corporate landlord has incresed. While there is no single cause for the Bay Area’s housing crisis (except, perhaps, greed), corporate consolidation and speculation have contributed to the increase in the cost of housing, which correlates with the significant increase of people experiencing homelessness in the Bay Area.

Read Hardship for Renters: Too Many Years to Save for Mortgage Down Payment and Closing Costs

In January of 2020, an organized campaign led by unhoused Black mothers in Oakland, Moms4Housing, successfully drew attention to how corporate speculation of homeownership was impacting low-income residents- including single moms and children. For weeks, the moms and their children lived in an empty single-family home in Oakland that Wedgewood had let sit empty, unoccupied. Listen to what happened next in the conversation below. California Housing Reporters interview Dominique Walker, one of the Moms4Housing, ACCE California Director and now Oakland City Councilmember Caroll Fife, and Aaron Glantz, a reporter that writes about the latest era of housing speculation.

Renters in Foreclosure: A Fresh Look at an Ongoing Problem

A 2012 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition about how renters were impacted by the foreclosure crisis.

The history that’s presented on this page is, of course, only part of the long and complex legacy of how housing inequity and homelessness came to be in the Bay Area. We encourage you to keep reading and learning!

The cruel, discriminatory past and sometimes present experiences of housing inequity and discrimination can be painful to learn about and reflect on how it shaped our life. Do know, there have always been activists and organizers pressing for positive change.

Each day, you have the opportunity to join alongside others in taking action. EBHO’s members and the organizations we collaborate with have been organizing and advocating for decades in the East Bay. We continue to gather together, across race and class lines, to enact changes that improve the lives of low-income communities and ensure a future East Bay with affordable homes for all.

For some inspiring content, read about the people and places of affordable housing communities in the East Bay — people who have a quality affordable home because of the advocacy of yesterday. Learn about how we build power and enact solutions together on our Building Power, Enacting Solutions page.