What is Affordable Housing?

“Affordable housing” refers to a high-quality, healthy home that fits within a household’s budget; each and every Bay Area resident deserves that.

On this page, we share information about what exactly is considered “affordable.” We explain the difference between types of community-invested affordable housing such as housing vouchers or public housing units. We also share information on different strategies used to fund affordable housing in California and how the state of California ensures cities determine land-use that includes affordable homes.

What is ‘Affordable’?

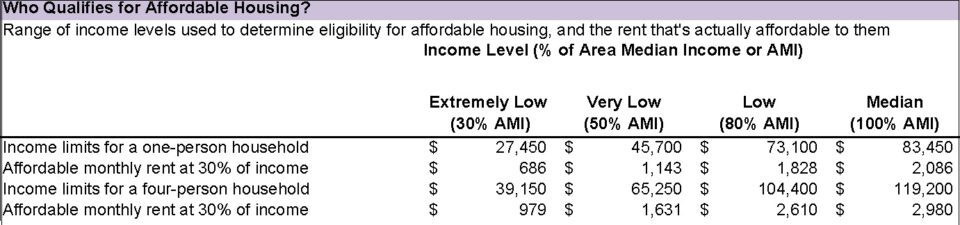

Housing is defined as affordable if it costs no more than 30% of one’s income. People who pay more than this are considered “cost burdened”; those who pay more than 50% are “severely cost burdened.” Affordable housing generally means affordable to lower-income people with incomes at or below 80% of area median income (AMI). Most affordable rental housing programs target lower-income people, while affordable homeownership programs increasingly target people making up to 120% of AMI. (See the chart below for income and rent limits).

Note that actual rents are often much higher, especially for newly built apartments.

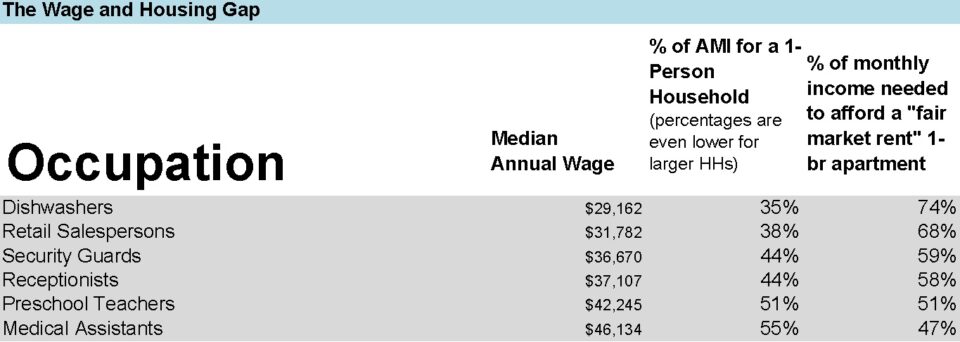

Wage information from California Economic Development Department for 1st Quarter 2020 (www.labormarketinfo.edd.ca.gov)

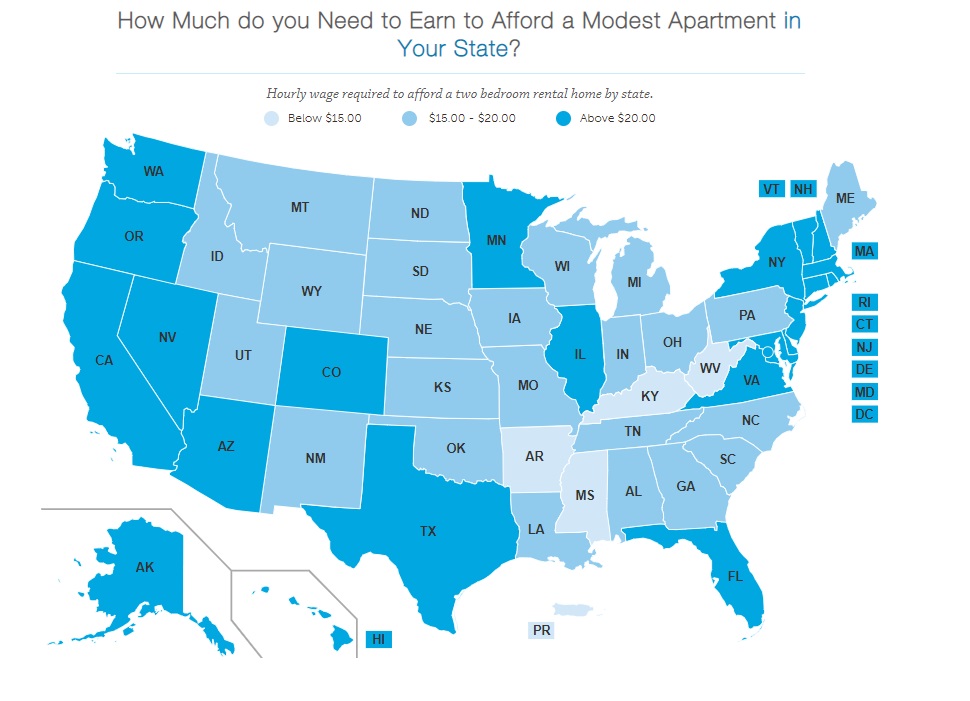

As the cost of housing has skyrocketed, even more people are unable to afford a home to live in without being cost-burdened. See the National Low-Income Housing Coalition’s Out of Reach 2020 Calculator:

How Much do you Need to Earn to Afford a Modest Apartment in Your State?

The 3P’s Approach

The fight for housing justice is inextricably linked to the fight for racial and economic justice. EBHO focuses on expanding housing opportunities for low-, very low- and extremely low-income people.

There is no “magic bullet” that will suddenly solve these problems. The solution lies in a comprehensive approach that includes the “Three P’s”: producing new market-rate and affordable homes; preserving existing housing that’s currently affordable; and protecting tenants from unaffordable rent increases and unfair evictions. EBHO leads and supports campaigns to address all three of these.

Production

- Requiring that all cities – particularly those that historically have blocked new housing – establish zoning for higher-density housing to accommodate their fair share of the region’s housing needs. For example, in 2020-2021, EBHO advocated for a Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RNHA) that promotes an equitable distribution of new housing and furthers fair housing.

- Expanding funding for affordable housing at the local, county, regional, and state levels. In 2020, EBHO supported ballot measures that won funding for homeless services and emergency housing in Alameda County (Measure W), and funds for affordable housing and other critical needs in Contra Costa County (Measure X).

- Using surplus public land to develop affordable housing. In 2019, EBHO helped pass amendments to the Surplus Land Act; we continue to advocate for full implementation of the amendments and to maximize the amount of affordable housing developed on BART-owned land.

- Ensuring that public actions that increase land values are coupled with requirements for affordable housing. For example, EBHO advocates for “land value capture” strategies in local plans like the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan.

Preservation

- Acquiring and preserving existing housing as permanently affordable. For example, EBHO was part of a coalition that passed AB 1079, which enables tenants and nonprofit organizations to match top bids on foreclosed homes, enabling existing homes stay in community control, preserving affordability by decreasing speculation.

- Preventing the loss of existing housing from condo conversion, demolition or use as short-term rental housing.

Protection

- Preventing excessive rent increases and unjust evictions.

- Providing counseling and legal assistance to tenants facing eviction.

Affordable Housing Types in the U.S.

In the United States, the system of housing is centered around housing as a market commodity; the high rates of homelessness and cost-burdened households are evidence that this system of housing is not working to meet the basic needs of its residents. Over the last 100 years, different tactics have been used to ensure that people with lower incomes can have a home they can afford with the resources they have. When people talk about “affordable housing” in the U.S., they’re generally talking about a home someone can afford with what they have available to them. For many middle- and upper-income Americans, homes bought or rented in the open market are affordable to them, meaning they spend less than 30% of their income on housing.

For the rest of the estimated 48% of renter households that are Housing Cost Burdened, other techniques must be used to ensure people can stay housed and afford the basic needs of their daily life. Below is a summary and links to other resources to understand the techniques that are generally used to extend affordable housing to people with below-median and low incomes.

Public Housing

Public housing is affordable housing for low-income households that is owned and operated by a public agency, known as a Public Housing Authority (PHA), rather than a nonprofit or for-profit developer. It is funded by the U.S. government through capital subsidies for construction and operating subsidies that limit rents to 30% of household income. First introduced in 1937, federal funding for public housing has come under attack since the 1970s. In 1998, Congress passed a law (known as the “Faircloth Amendment”) barring PHAs from building more units than the number they owned in 1999. Federal disinvestment in public housing has led to the deterioration of PHA properties and widespread housing insecurity among low-income people. As such, progressive policies like the Green New Deal now call for a renewed federal investment in public housing as part of a larger program of social housing.

Read more about EBHO leaders that live and lead in Public Housing here in the Bay Area.

How did public housing get a bad reputation as a “bad” place to live? Disinvestment, meaning the Federal Government didn’t keep its commitment to fund the upkeep of these properties, is the simplest answer, but we recommend these articles to better understand the range of disinvestment in public housing. Some public housing units have benefitted from rehabbed housing and are quality places to live, but the total number of public housing units was frozen under the Faircloth Amendment and level of affordability reduced under the federal Hope VI policy. Despite this, public housing remains home to hundreds of thousands of people in the United States.

20 Years Later, What Hope VI Can Teach Us (Shelterforce, 2017)

What is the Faircloth Amendment (Next City, 2021)

Nonprofit Affordable Rental Housing

In public policy, housing is considered “affordable” when the household pays no more than 30% of their overall income in housing costs. For rental units, housing costs typically include rent and utilities. The term “affordable housing” usually refers to housing that is affordable to low-income or moderate-income households in particular.

There is no set cost that makes a home affordable to all people. Rather, the exact amount that is affordable can change significantly relative to household income. For instance, a single elder living off of a fixed income will be able to afford far less than a family with two adults who work as teachers. If a household pays more than 30% of their income on housing costs, then they are considered to be cost burdened. Both renters and homeowners can experience cost burden, regardless of their income.

Nonprofit, mission-driven affordable housing organizations provide an affordable home for hundreds of thousands of families, elders, workers, and people with disabilities in the U.S. Nonprofit affordable housing providers combine public investments from taxes, bonds, grants, and fees with private-market financing to build new affordable home and rehabilitate properties that are in disrepair. Then, they rent those units to low-income residents, usually charging no more than 30% of their income. That rental payment is used to upkeep the property and pay staff that help operate the communities and create more affordable homes.

Nonprofit affordable homes provide a foundation for our communities. Read stories of EBHO resident-leaders that live in nonprofit affordable homes or view EBHO nonprofit developer members’ new and rehabilitated homes throughout the East Bay.

A California state law, Article 34, prevented affordable public and nonprofit homes from being built in majority-white, high-income communities for decades. Article 34 prohibits the building of affordable homes in a community without the majority vote of residents to allow it. While state laws to incentivize affordable housing generally take precedent over this Article now, the racist and classist law is part of a long legacy of housing discrimination against low-income people. Read more about this law and attempts to repeal it.

Housing Choice Vouchers (Section 8)

Housing Choice Vouchers (HCVs)/Section 8: HCVs, often referred to as “Section 8,” are subsidies that ensure that low-income households pay no more than 30% of their income in rent. The voucher is used to pay the landlord the difference between the full rent and the amount that is affordable to the tenant. The HCV program is funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and run by Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) in local communities. HCVs may be tied to either specific tenants or specific housing units. A household with a “tenant-based voucher” can move from one apartment to another and the subsidy will move with them. A housing provider with a “project-based voucher” can subsidize a specific unit in order to make it affordable to successive low-income tenants. When a tenant leaves an apartment with a project-based voucher, the subsidy will not move with them.

Read about an EBHO leader whose life has been stabilized and supported with a tenant-based housing voucher.

Read more about the Housing Choice Voucher Program and Project-Based Voucher Program from NLIHC Advocate’s Guide.

Affordable Homeownership Programs

In public policy, housing is considered “affordable” when the household pays no more than 30% of their overall income in housing costs. The unit can be either a rental or ownership unit, such as a condo or a single-family residence. For rental units, housing costs typically include rent and utilities. For ownership units, housing costs can include mortgage payments, property taxes, insurance, utilities, and condo fees. The term “affordable housing” usually refers to housing that is affordable to low-income or moderate-income households in particular.

There are programs in most counties and cities to encourage low-income homeownership, including

More information on Affordable Homeownership Programs in California and the East Bay:

https://www.hud.gov/states/california/homeownership/buyingprgms

View Resources on Mortgage Lending from the Center for Responsible Lending.

Community Land Trusts

A Community Land Trust (CLT) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to buying properties in order to maintain them for communal uses, including farming, gardening, and affordable housing. In a residential land trust, the CLT owns the land while residents rent or own the buildings on that land. This makes it so that residents continue to live in their homes, often at an affordable cost, while the land remains a long-term asset under community control. Community control ensures that, once the current residents move, the housing will remain permanently affordable to other residents of the neighborhood. CLTs are thus a tool to fight gentrification and displacement. In addition, they can help residents build financial wealth through ownership of their homes or apartments, also known as the “improvements,” but not the land itself.

See more information on community land trusts on our Study Room page, Building Power, Enacting Solutions.

Market-rate Affordable Units

The cost of market-rate housing rises and falls with changes in the value of real estate, or what consumers are willing to pay. It is not set according to the guidelines of government agencies, which do not directly finance market-rate housing. As such, market-rate housing is more expensive than community-invested or what’s often called subsidized affordable housing, where housing costs are capped to fit the budget of low-income households. Most for-profit developers build market-rate housing, while nonprofit developers build affordable and supportive housing.

The vast majority of rental listings that are available when a person searches for an apartment are market-rate rental housing, and the rules vary city-by-city how much a landlord/housing provider can charge for rent after the previous tenant has left the unit. There are also different rules about how much a landlord can increase the rent each year on existing tenants, though since January of 2020 in the state of California, many market-rate units are subject to a rent cap and just-cause eviction rules. This comes after many years of powerful tenant advocacy from housing-justice organizations, including EBHO.

Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH): NOAH is a term for lower-cost rental homes that do not receive a direct government subsidy. The landlords are not required to limit rents to make them affordable, but they charge lower rents regardless. These homes are relatively affordable to low-income households due to landlord choice, rather than regulatory requirement. While NOAH provides homes to many who need it, the lack of rent regulation means that the landlord can increase the rent at any moment (unless there is rent control and strong tenant protections). As a result, many advocates call for NOAH to be “preserved” through programs that allow tenants or nonprofit organizations to purchase these homes using a subsidy and, in exchange, restrict the rents to make them permanently affordable to lower-income residents.

Condo-Conversion Ordinances: EBHO was part of a coalition of organizations that successfully updated the City of Oakland’s Condo Conversion ordinance to prevent tenant displacement and slow the total number of rental homes, including rent-controlled homes, that were being converted to Condominiums and sold. The overall reduction of the number of rental properties in the city, especially those eligible for rent caps and rent control, drives up the cost of rental housing over time.

Policies Impacting Housing Affordability

Rent Control

Rent control is a policy that limits the amount that a landlord can raise the rent in a given year. It serves to stabilize housing costs for low-income households who do not live in rent-regulated affordable housing. It also discourages speculation in low-income neighborhoods, where rising rents lead to gentrification and displacement. In California, however, the Costa-Hawkins Act weakens rent control by letting a landlord raise the rent when a new tenant moves in. This encourages landlords to evict tenants who live in rent-controlled units. Just Cause eviction protections are needed alongside rent control to discourage this practice.

The Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act

The Costa-Hawkins Act, passed in 1995, is a California law that limits the ability of local communities to adopt or strengthen rent control. It prohibits cities and counties from enacting laws that restrict the rent on 1) vacant units (though subsequent rent increases can be regulated), 2) single-family homes or condos, and 3) units built after 1995 (or earlier, in some cases). Housing justice advocates have long sought to close the loopholes in local rent control laws created by the Costa-Hawkins Act. But two recent ballot measures (Prop 10 in 2018 and Prop 21 in 2020) failed to receive 50% of the vote.

Read more about the campaigns to repeal the Costa-Hawkins Act:

https://www.tenantstogether.org/campaigns/repeal-costa-hawkins-rental-housing-act

https://la.curbed.com/2018/1/12/16883276/rent-control-california-costa-hawkins-explained

Eviction Protections

Eviction is the process of removing a residential or commercial tenant from where they live or do business. There are five stages of the formal residential eviction process. It starts when a landlord issues a notice warning the tenant that they are no longer allowed to stay in their home. It moves through a legal trial known as an “unlawful detainer” (UD) case. And it ends with law enforcement physically removing the tenant and their belongings. (The reasons that a landlord can legally evict a tenant are limited in most cases in California by state and local protections known as Just Cause for Eviction.) Evictions often increase with gentrification, leading to the displacement of low-income residents and communities of color. However, they are also common among cost-burdened renters who struggle to afford the high cost of market-rate housing. The individual and communal costs of evictions are high. In the Bay Area, eviction can lead to homelessness. Rent control, Section 8 vouchers, subsidized affordable housing, and eviction moratoria are all tools to reduce the likelihood and harms of eviction.

In 2020, EBHO and coalitions across the state advocated for an won eviction moratoriums at the county, city, and state levels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eviction Moratoria

An eviction moratorium is a temporary prohibition on evicting, or removing, a residential or commercial tenant from the space that they rent. While such laws are rare, they have become more common during the pandemic because, without them, millions of renters who lost work would be displaced from their apartments, thus making it harder to control the spread of COVID-19. To be truly effective, an eviction moratorium should outlaw all five stages of the eviction process. But AB 3088/SB 91, the statewide eviction moratorium passed in response to the pandemic, only restricts a landlord’s ability to take a tenant to court in what is called an “unlawful detainer” (UD) case. Some local governments, including Alameda County, have passed moratoria that are stronger than the statewide law, offering local residents more protections. You can learn more about the emergency eviction protections in your East Bay community here.

Read More:

The Coming Wave of COVID-19 Evictions: A Growing Crisis for Families in Contra Costa County. by By Jamila Henderson, Sarah Treuhaft, Justin Scoggins, and Alex Werth (East Bay Housing Organizations). July 2020

Navigating the Eviction Process and its Lasting Impact (by Dana Bartolomei, Shelterforce, 2020)

Funding Affordable Housing

Impact Fees

Impact fees are paid by developers to local governments to offset the cost of meeting the increased need for public services generated by those developments, including transportation, fire protection, and affordable housing. Housing impact fees can be used to ensure that residential development for higher-income households creates the resources needed to build homes that are affordable to the lower-income workers who provide the basic goods and services to the community. Housing impact fees can also be charged on office and commercial developments. The amount of an impact fee must be based upon an analysis of the “nexus,” or link, between the new development and the increase in demand for public resources. This analysis is called a “nexus study.” The resulting fee is thus also called a “linkage fee.”

Read our Op-Ed on Impact Fees by EBHO Executive Director, Gloria Bruce. Opinion: Oakland Should Turn Cranes Into Affordable Housing.

Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC)

The LIHTC program (pronounced lie-tek) is used to raise money to build affordable homes. First, the federal government issues income tax credits to a developer, which correspond to the costs of building affordable units. Then, the developer sells those credits to private investors, who can use them to lower their federal income taxes. This helps the developer raise capital for their project and reduces the amount of debt that they need to borrow from a bank. Less debt means the developer can charge lower, more affordable rents to low-income households. The LIHTC program was introduced in 1986 to get private investors, rather than government agencies, to help pay for affordable housing. It is now the primary source of funding for affordable housing — especially projects that serve households at or below 60% of AMI, which are the main recipients of LIHTC.

Housing Bonds

Federal housing bonds are used to finance lower interest mortgages for low- and moderate-income homebuyers, as well as for the acquisition, construction, and rehabilitation of multifamily housing for low-income renters. Investors are willing to purchase tax-exempt housing bonds and receive a lower interest rate than they would for other investments because the income from these bonds is tax free. Read more about what federal housing bonds are and how they’re financed from the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s 2021 Advocate Guide.

A general obligation bond is a government-issued bond that is repaid from state or local general funds or a dedicated tax. The issuing entity (e.g., the city, county, or state) places its full faith and credit in paying back the purchasers of the bond. Money from general obligation bonds can be used by counties or states to provide subsidies for affordable housing projects or fund other affordable housing programs. Learn more about general obligation bonds.

In November, 2016 EBHO was part of a campaign to pass Measure A1 Affordable Housing Bond in Alameda County. Read more about how A1 was designed to create affordable homes for low-income residents. Homes funded with Measure A1 Bond measures have started welcoming residents home. You can view A1-funded properties that had or have rental listings at https://housing.acgov.org/listings.

The National Housing Trust Fund (HTF)

“The primary purpose of the HTF is to close the gap between the number of extremely low-income renter households and the number of homes renting at prices they can afford. NLIHC interprets the statute as requiring at least 90% of the funds to be used to build rehabilitate, preserve, or operate rental housing (HUD guidance sets the minimum at 80%). In addition, at least 75% of the funds used for rental housing must benefit extremely low-income households. One hundred percent of all HTF dollars must be used for households with very low income or less.”

Read more about this program in the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s 2021 Advocates Guide