We know what ends homelessness. The research is clear — homes people can afford, with equitable access and support if they need it — will end homelessness in the United States. If we use the power we have as a community to advocate and organize to keep people housed, create new affordable homes for very low-income people, and invest in each others’ well being, we can end homelessness.

Read on to learn more about solutions to homelessness in the U.S. and the East Bay.

Table of Contents

Our Current Conditions

In California, more than 150,000 people were counted as unhoused on one night in January, 2019. More than half a million people in the U.S. are currently unhoused, and that number under-represents the number of people living without adequate housing.

View the California Housing Partnership California Affordable Housing Needs Report 2021: https://chpc.net/resources/california-affordable-housing-needs-report-2021/

Homelessness in Alameda County

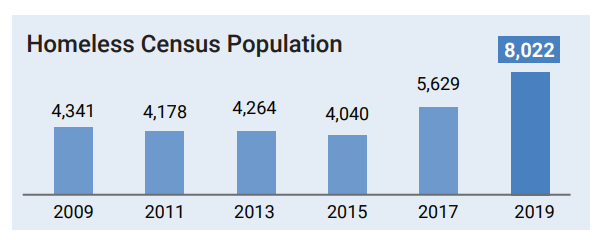

On the morning of January 30th in 2019, teams of community service providers and volunteers in Alameda County, California counted 8,022 individuals sleeping in a place “not intended for regular sleeping accommodation” such as a tent encampment, car, or the street or living in a temporary supported living facility such as a shelter or transitional housing facility.

This was an increase of 2,393 individuals, 43% more than in 2017, the previous time the count was conducted. We don’t yet have the reported numbers for 2021 (it was delayed a year because of the coronavirus pandemic) but residents of the East Bay can see that the number of people visibly living in an inadequate shelter has grown. This increase is also reflected nationally.

Homelessness in Contra Costa County

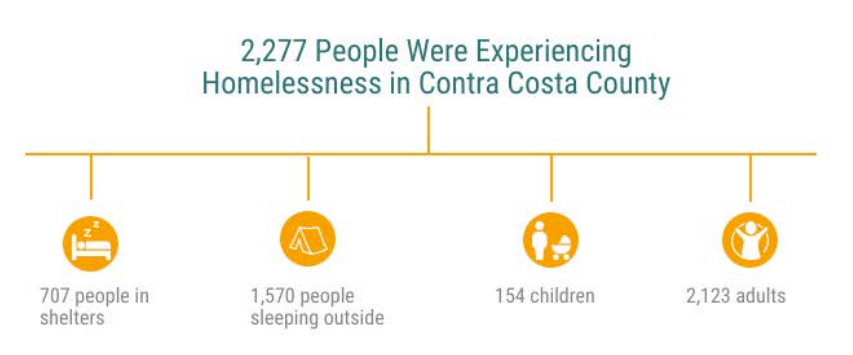

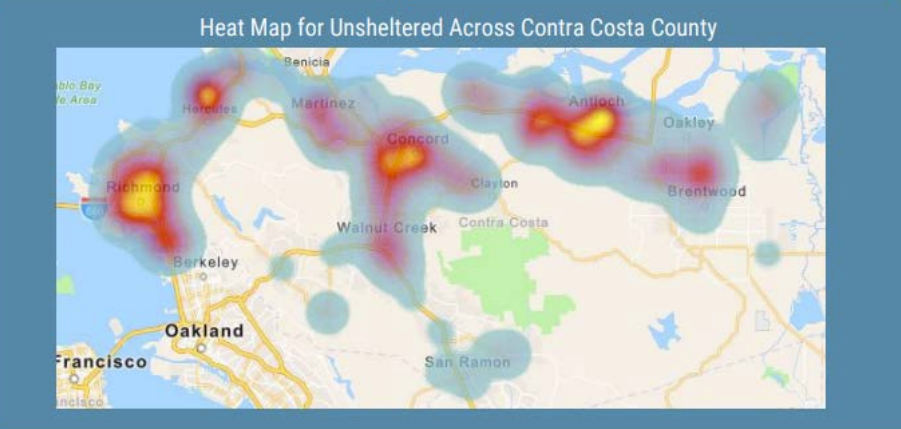

The Contra Costa County 2020 Point in Time count identified 2,277 total individuals sleeping in shelters, outside, or in uninhabitable locations on January 20, 2020. Just under one-third were sheltered (707) and more than two-thirds were unsheltered (1,570).

Causes of Homelessness

Homelessness in the U.S. in its current form has grown consistently since cuts to public supports in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which accelerated in the Reagan Era. As the thin safety net for low-income people in America deteriorated, this era has also been a time of ongoing transfer of wealth to the richest and the privatization of public resources.

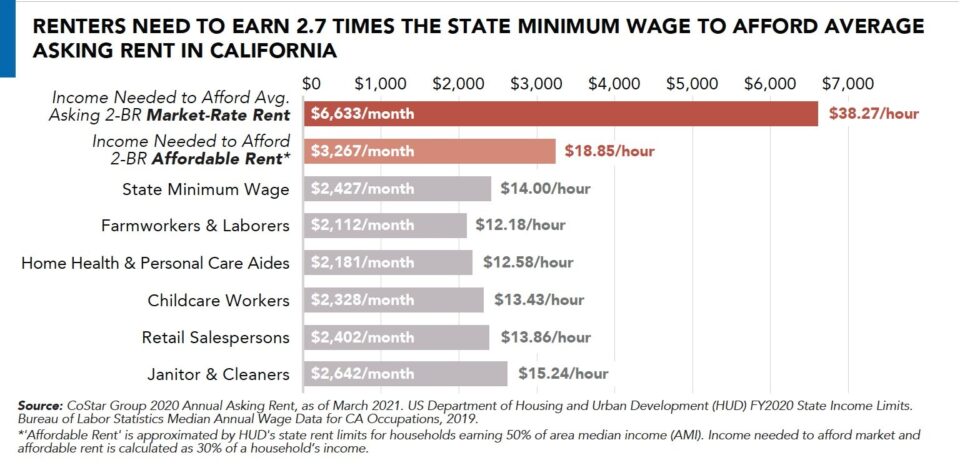

The National Alliance to End Homelessness has compiled decades of research to show that Homelessness in the U.S is caused by a lack of housing that low-income people can afford with the funds they have available. The economic reasons for the gap between housing cost, access, and wages are caused by multiple intersecting reasons: Many workers are not paid enough to meet their basic needs; the cost burden of housing in the U.S. continues to rise; and too few people are able to access quality affordable healthcare, including mental healthcare, resulting in disability and causing significant financial burdens.

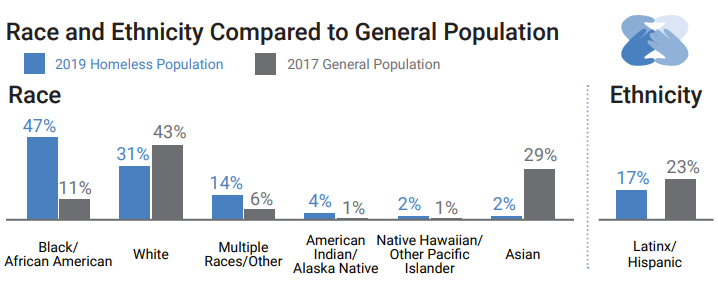

Unequal treatment based on race — racial disparity — deprives too many Black and brown people of fair wages and opportunity, including the opportunity to accumulate a safety net and cushion of wealth across generations. This results in Black and Indigenous low-income people experiencing homelessness more than white people. Violence — interpersonal violence, childhood abuse, military violence, and other forms of state violence such as mass incarceration — are correlated with homelessness far more often than those who do not experience trauma from violence. People with disabilities, transgender, and gender-non-conforming people also experience homelessness at much higher rates than people who do not experience ableism or discrimination based on gender expression. Evictions are often the beginning of a string of inadequate housing that results in homelessness, especially for single mothers and their children.

Unfortunately, people who are unhoused experience a increased likelihood of violence, including hate crimes, during their time living unsheltered.

Summary

- High cost of housing, resulting in a lack of housing that’s affordable to low-income people

- Economic Inequality

- Discrimination including

- Racism in housing, the economy, and all areas of life

- Ableism

- Homophobia & transphobia

- A weak social safety net providing quality healthcare for all, food assistance when people fall on hard times or emergency economic assistance

- Violence, including the violence of war, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and intimate partner (“domestic” violence)

- Incarceration & discrimination against formerly incarcerated people in housing

Because we have not yet created the economic and social safety net our communities need, currently a few difficult experiences can result in just about anyone, no matter what race, ability, or gender identity they are, finding themselves without a safe stable place to come home to. However, it is entirely possible to make homelessness brief and rare, a future in which our neighbors sleeping on the street in masse is a tragic time period in our memory.

What ends homelessness?

At EBHO, we advocate for affordable homes for all low-income people in the East Bay by protecting existing tenants who live in homes they can afford, preserving existing affordable homes, and producing new affordable homes for the tens of thousands of East Bay residents that so critically need it. Still, as the gap between housing prices and low-income people’s wages grows, more people are unhoused each year. We advocate for proven solutions to help people who are currently unhoused get stable housing and prevent people from losing their existing housing.

The research is clear that rising housing costs correlate with an increase in people experiencing homelessness. A quality home a person can afford with the funds they have available is the solution to ending homelessness, even if the person or family needs extra support at first.

There are different terms used to describe the kinds of housing interventions used to help people who are currently unhoused or at risk of homelessness. Learn more about the different types of interventions, and why most communities use a combination of techniques to address differing needs.

Rapid Rehousing

Research shows clearly that keeping families in their homes through temporary emergency rental assistance is effective in keeping low-income families from living in shelters or on the streets, enchanting the health and wellness of the family and saving taxpayers money that would be needed for homeless services. Research shows similar wellness and financial impact when communities provide rapid re-housing by providing one-time emergency funds to secure housing, such as a rental deposit or tapered rental assistance in the early months for a family with an income in order to secure an apartment they can afford.

Housing First

Housing First is an approach that is shown to most effectively end homelessness for people who have been unhoused multiple times in their lives, or for more than a year. Housing first is an approach in which communities provide the housing that unhoused people need without conditions of sobriety or adherence to medical interventions. The United States has a long history of requiring adherence to rules and norms before providing housing to people who need it. Over and over again, it’s proven to be a barrier to housing people, forcing people to remain unhoused because they’re unable or unwilling to adhere to norms, such as sobriety, that many housed people do not conform to. What’s more, it is a waste of public money.

In 2020, during the COVID-19 Pandemic, the State of California released federal funds for counties and cities to rent entire motels and hotels to use as non-congregate shelters for unhoused people with medical conditions that made death from COVID-19 more likely. This program, “Project Roomkey” is a type of housing-first intervention. Some municipalities used Project Homekey funds to permanently buy hotels or other properties to use as single-residence-occupancy to house people who were sheltered in the Project Roomkey program. In the video below, Terrell Hegler of Bay Area Community Services talks about the program and the house in Oakland that will be a new home to many using a single-room occupancy (SRO) model of sharing common spaces while renting a single room.

Listen and read about Housing First as a proven approach to ending homelessness:

- Listen to the podcast episode from, 99% Invisible: According to Need – Housing First.

- Project RoomKey: Read about the success of people who were given shelter in a setting that allowed privacy and access to a private bathroom via the federal COVID-19 response program, Project Roomkey:

- Alameda County Project Roomkey Success Stories

- Listen to “Hotel Corona” on Sold Out: Rethinking Housing In America (KQED) and the updated episode sharing what happened a year later.

Coordinated Entry

Currently, the Alameda and Contra Costa Counties (the East Bay Counties) use 211 as a switchboard for people in need of social support, including emergency housing. The 211 program is one pathway to what is called “coordinated entry.” Coordinated entry, also known as coordinated assessment or coordinated intake, is a process designed to quickly identify, assess, refer, and connect people in crisis to housing and assistance, no matter where they show up to ask for help.

Listen to a story of how Coordinated Entry/211 works in Alameda County in this Podcast: According to Need: The List

Connect with 211/Coordinated Entry Support in Alameda County or Contra Costa County.

View the National Alliance to End Homelessness’s webinar on coordinated entry and systems change.

Supportive Housing

In a nation plagued by inequity, structural racism, an immigration system that fractures families, and violence – be it from war, gendered violence, childhood abuse, or state violence from police and jails – have resulted in a profound need for extra mental and physical health care for people who are housed and too often, for people who are unhoused. We all need more connection and care for each other. Sometimes, unhoused people need extra support to re-stabilize their life in a new home.

Transitional Housing is a type of housing where program participants have signed a lease or occupancy agreement, with the purpose of facilitating individuals and families’ ability to move into permanent housing within 24 months or less. Wrap-around services, sometimes including case management and financial support, are usually included.

Rental Assistance – “Section 8” Housing Vouchers

Federal Rental Assistance Fact Sheet from the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities

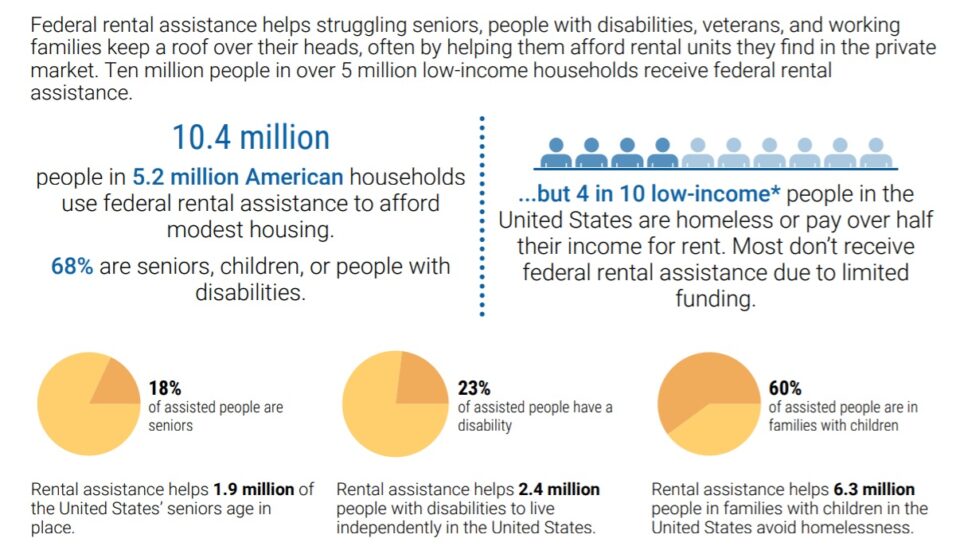

Rental assistance clearly works to offset the difference between what landlords charge for rental housing and the cost low-income people- seniors, families with children, and disabled adults – are able to pay with the funds they have. Federal rental assistance is often called “Section 8” or a “Housing Voucher.”

Research Shows Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship and Provides Platform to Expand Opportunity for Low-Income Families – Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP)

Housing vouchers are a long-term intervention to help people get housed and stay housed. However, emergency rental assistance is key in preventing people from losing their housing, the most cost-effective way to address homelessness and keep people stable, healthy, and connected to the school stability and community networks people need to thrive.

More Resources

Podcasts

Reading

Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people by the Prison Policy Initiative, 2018

The Role of Long-Term, Congregate Transitional Housing from the National Alliance to End Homelessness

Alameda County Department of Housing & Community Development Transitional Housing Programs

Opening Doors to Unhoused Applicants by Chris Hess, Former VP of Resident & Community Services at SAHA

How Rising Rents Contribute to Homelessness A new report shows rent increases in expensive cities can make the homelessness rate rise faster. By Gaby Del Valle, Vox, 2018.

Homelessness Rises Faster when Rent Exceeds a Third of Income By Chris Glynn – Alexander Casey on Dec. 11, 2018. Based on “Inflection Points in Community-Level Homeless Rates” in the Annals of Applied Statistics. By Chris Glynn, Thomas Byrne, and Dennis P. Culhane. 2021.

Out of reach 2020 from the National Low Income Housing Coalition

Learning from Emergency Rental Assistance Programs: Lessons from 15 Case Studies from Housing Initiative at Penn, National Low Income Housing Coalition, and NYU Furman Center

The Impacts of Homelessness Prevention Programs on Homelessness – Evans, Sullivan, and Wallskog in Science Magazine, 12 AUGUST 2016 • VOL 353 ISSUE 6300

Homelessness Prevention Programs Improve Outcomes and Save Money – National Low Income Housing Coalition

Homelessness Prevention: A Review of the Literature – From the Center for Evidence-Based Solutions, January 2019.

Strategies for Preventing Homelessness – U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research, prepared by Martha Burt, Urban Institute (2005)

Rapid Re-housing Works: What the Evidence Says National Alliance to End Homelessness (2018)

Rapid Re-housing’s Role in Responding to Homelessness – Cummingham & Batko, Urban Institute.